The Charger Blog

Charger Blogger Enters Final Semester with Excitement and a Plan

Beatrice Glaviano ’26 reflects on EMT life, learning assistant work, and what she hopes to carry into her final semester.

The Charger Blog

As part of a groundbreaking program supported by the Davis Educational Foundation, a group of exemplary professors are designing courses with their students. They reflect on the experience and the experience and impact they are endeavoring to make.

November 17, 2021

As part of the University of New Haven’s Open Pedagogy Project, nine exemplary faculty members have been creating new course materials designed to foster exciting and engaging opportunities for students.

A faculty development fellowship program supported by the Davis Educational Foundation and the William L. Bucknall Excellence in Teaching Award, the Open Pedagogy Project was developed in 2020 by English professors Mary Isbell, Ph.D., and Jenna Sheffield, Ph.D. It is now co-directed by Dr. Isbell and Matt Wranovix, Ph.D., who is among the inaugural group of Faculty Fellows.

The Open Pedagogy Project endeavors to empower faculty to design courses both for and with their students and help faculty members create resources they can use in the classroom and share with each other.

Below the 2021 Faculty Fellows reflect on their work and on the impact they hope it has on students.

It was with great excitement that I applied for the Open Pedagogy fellowship this past spring. I have a high appreciation for any project that is innovative, agile, and targeted to create a learning community.

It has been such an honor to be a member of the Open Pedagogy community, and to engage this past summer in learning about Open Education Resources (OER) and how to use them to empower our students.

To me, open pedagogy (OP) is a teaching philosophy that puts students at the center of learning and considers them as co-creators of knowledge. It fosters their engagement and recognizes their voices as a way to reinforce inclusivity, innovation, and social justice.

The use of free OER is critical in open pedagogy to facilitate and amplify access, especially for underprivileged students. There are already studies providing evidence of the impact of OER on cost-savings from textbooks and other course materials.

As soon as I embarked on this journey, I reminded myself of the need to embrace courage and enjoy the participatory process. Meeting with my colleagues every two weeks to discuss our progress and learn from each other was so liberating and rewarding. I will describe below the early outcomes of my participation in this OP program.

I designed an experiential and interdisciplinary term project in which graduate business and healthcare students can collaborate with faculty members to develop a teaching case on inclusion in a healthcare organization during these trying times of COVID-19. This project aims to foster synergy between open pedagogy and open scholarship while promoting multidisciplinary collaboration between students and faculty.

My colleague Dr. Yanice Méndez-Fernández, interim associate dean and assistant professor in the School of Health Sciences has been very excited about this collaboration and invited Samantha Morales, interim director of the Master of Healthcare Administration program, to join this effort. The project will foster partnership between faculty, students, and practitioners and can be easily emulated by other faculty members.

After spending the summer learning about OP and OER, I felt ready to get rid of the textbook in MGMT3350: Management of Workforce Diversity that I am teaching this fall. Besides including a statement in my syllabus about OP and OER, I used the first session of class to explain OER and the rationale behind using them. In addition, I asked the teams I composed to think about how they imagine an open and inclusive classroom. I have already used links to openly licensed materials in the first module, and I will be adding more as the course progresses.

In almost every module, students are invited to find an open education resource that is aligned with a learning outcome of their choice. Another key assignment is to develop a story/critical incident pertaining to discrimination, inequity, exclusion, oppression, etc. following a template that I provide. Students will share their work and will be invited to facilitate a class discussion on their chosen theme.

To enable students’ engagement in OP, I have already posted on Canvas links to general OER they can start using. Diane Spinato, the liaison librarian to the Pompea College of Business, will be visiting my classes and sharing the library guides she prepares and updates every semester for all my classes. This time she will be adding OER that are aligned with the content of my courses.

As I enjoy the benefits of this process, I am already thinking about how to sustain the open pedagogy movement and how to engage all constituents in this process. An initial project I have just embarked on with the help of Diane Spinato is to create a repository for the Department of Management and invite my colleagues to review and select the resources they wish to use in their courses.

Finally, I highly value the collaborative learning that has been taking place in our community of practice. I am looking forward to students’ reactions and feedback this semester.

As I reflect on my journey as an Open Pedagogy Fellow, I am highly satisfied with my progress to date. From the start, my goal was to redesign the delivery mode in my General and Oral Pathology course from a traditional lecture format to a more student-centered and engaging one.

Furthermore, I envisioned creating course content that incorporates active learning strategies and high-impact teaching strategies, with dental hygiene student collaborators as guides. With perseverance and excitement while learning Html-5-Package (H5P), a plugin tool that helps produce and run interactive content and interactive video within a learning management system, I accomplished my goal – and then some. Hence, how did my Open Pedagogy Fellowship journey begin, and where am I today?

I started my journey by reading the information about What is Open Pedagogy? posted on the University of New Haven Open Pedagogy homepage. Continuing my learning adventure, I accessed the OER Examples page. There I found the answer – Building Interactive Resources — Branching tree skills practice. This link brought me to the H5P, a technology that is an open resource that provides users with ways to build and author interactive content. I had an aha moment! I read a great deal about how to use the H5P technology and its application in the classroom.

I then invited my senior dental hygiene student collaborators to weigh-in. Did they think that the H5P technology would change the delivery mode in my General and Oral Pathology course? Would it deepen the students’ learning? Would it satisfy the multi-modal learner? Would it engage the students in the classroom? And, most importantly, would the H5P technology be easy to learn and easy to integrate into my lectures? My student collaborators agreed that this technology seemed to perform all of the above.

After having several meetings and email exchanges with an H5P representative, in which I learned about H5P technology and its integration into course work, my student collaborators and I became more intrigued by the learning process. From that day forward, we adhered to an agenda and a timeline. The agenda consisted of the selected pathologic lesions and conditions to be highlighted in the interactive content.

As we worked together, a democratic process ensued about the development of the interactive content, images, videos, and assessments. It was truly an enlightening process while collaborating with my dedicated seniors. They were always focused and always encouraging – smart, too!

From a productivity standpoint, we created a mix of interactive content. Although the H5P technology has its limitations and nuances, we found the technology to be intuitive and engaging. Relative to its learning curve, most time was spent reviewing the tutorials to guide the creation of the interactive content. In addition, we spent time learning about searching for open content (videos and images) and the Creative Commons copyright licenses.

Where am I today? I intend to trial the H5P interactive content in my General and Oral Pathology course this fall. I am optimistic about its success in the classroom, and I anticipate that the H5P technology will increase student engagement and retention of content for its application in clinical practice.

What are the next steps with H5P? My hope is to create more interactive content for my General and Oral Pathology course, to upload all of the content in the H5P OER Hub, and to integrate the H5P technology directly into Canvas. Lots to do and lots to learn!

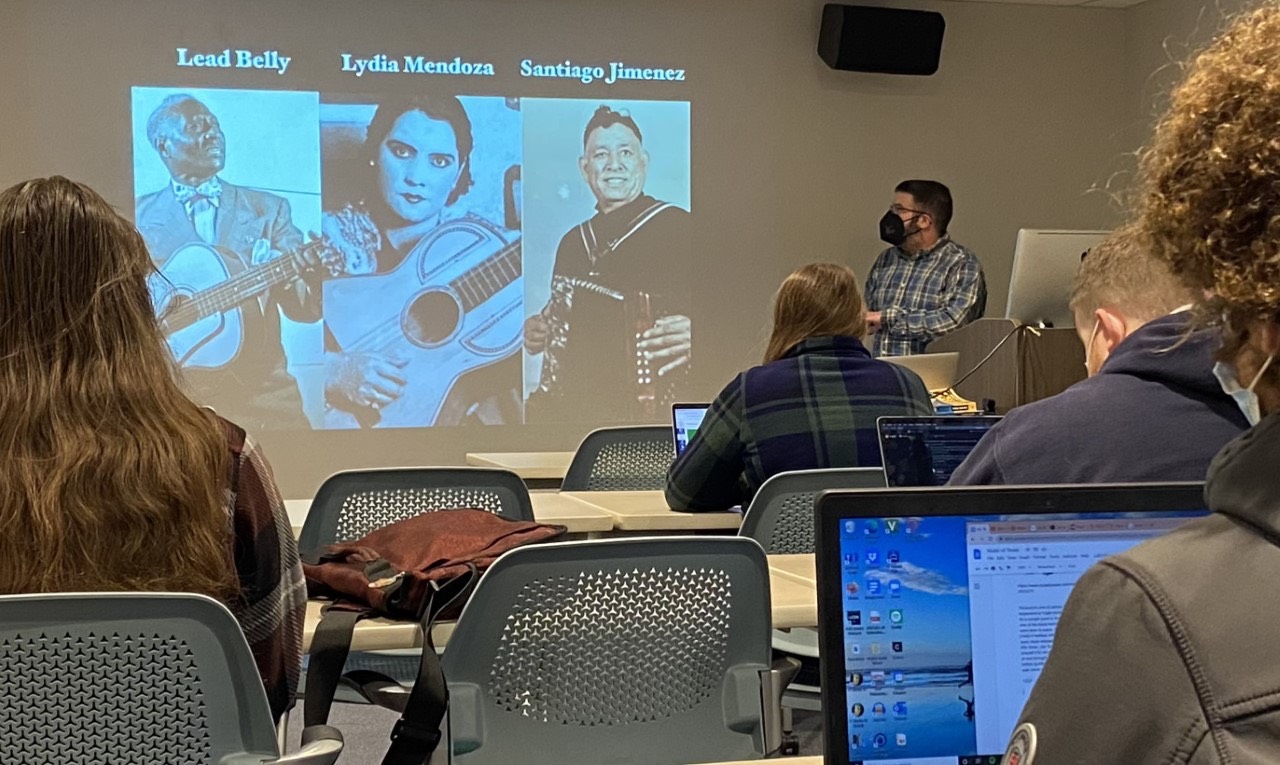

It was a very productive summer for me as an Open Pedagogy Fellow. After a few months of meetings, readings, and exchanging inspirational ideas with my colleagues, I’ve finally managed to craft a syllabus that looks unlike anything I’ve ever produced. The course is “Music of Texas,” and this semester is the first time I am teaching it. My work this summer with Open Pedagogy has deeply informed the design of “Music of Texas,” from assessment to assignments, and even the nature of our time together in the classroom.

The first day of class was scarier than usual for me, as I had to get students excited about a new course and on board with an experimental new course format. I shared my carefully written syllabus, explained exactly why I was doing things differently than they were used to, and acknowledged that they were each going to have to be willing to experiment alongside me. I reminded students that “new styles of teaching” (for me) will also mean “new styles of learning” (for them). So far, my “Music of Texas” students seemed receptive to the idea of Open Pedagogy as I’ve explained it.

I had originally imagined I would ask students to work toward creating a publicly-available podcast as a summative semester-ending project. But after a few meetings with my Open Pedagogy “course-development group” (CDG), I realized that a student-developed website would be a perfect repository of the work that we do in class over the semester — and equally easy to share with the general public when the semester is over.

A website allows students to generate work in a variety of multimedia formats, which — in this course — will include written texts, but might also include embedded audio (student-created podcasts, original songs, samples of classic Texas music), video (existing YouTube videos about Texas history, culture, or music or student-created “explainer videos”), and archival/primary-source images related to the themes of the course.

I’ve worked to design assignments that strike an appropriate balance between structure and freedom. I want to provide guidance for my students (so they know what the larger task is), but I also want to leave room for them to experiment and discover. I want students to “go with the flow” if their research changes direction midway through their process, and to celebrate their own curiosity. That might mean following their muse, rather than a strictly-worded assignment prompt.

My work with Open Pedagogy has stimulated this kind of flexible approach, and it encouraged me to think about centering assignments around students (and their interests) rather than around some particular specific “content” that I’d like to make sure that students learn. Instead of designing this course around lectures or readings, I’ve designed it around a series of assignments that use a “jigsaw” strategy: each student studies a different topic (one they can opt to select on their own), and then, in class, we can learn from each other’s research.

I’ve spent so many months with versions of this course in my head, and it’s exciting (and scary!) to see it as a real thing, out in the real world. I’m eager to see how the course will continue to develop now that it’s a shared classroom experience, one that is no longer 100 percent under my control. And, of course, I’m grateful to the Open Pedagogy Fellowship (and to my fellow Fellows) for helping me get more and more comfortable with this sharing of control.

Participating in Open Pedagogy this summer provided me with an opportunity to reflect on myself as an educator, a peer, and a student. I recently finished my Master of Public Health degree at the University, and I found that I learned the most from case studies.

For my open pedagogy project, I chose to design a case study with an interdisciplinary focus to use in a new course: Introduction to Public Health. Because public health is by nature intersectional, I wanted to introduce students to public health approaches to infectious diseases in the context of history, while incorporating the contributions of other areas of study. The case study is a scaffold on which we can incorporate theories, frameworks, and perspectives from other disciplines so that the resource can be adapted to use in different classroom settings.

To build the first case study I collaborated with Dr. Rosemary Whelan, an associate professor in the Biology, Chemistry and Math department at Albertus Magnus. This experience was great because I was able to receive content and feedback from an educator who already uses open- access resources in her courses and engages in high impact practices in the classroom. We decided to use the Soft Chalk platform for several reasons.

Soft Chalk is a platform we are both familiar with and have used in many other courses. It allows the instructor to design lessons with activities and questions that link easily to the assignments and grade book in Canvas and Blackboard. Soft Chalk does require an instructor to have an account, but once the material is created, students can access it freely. Content created on Soft Chalk can be available as openly licensed material under a creative commons license.

For the design of the first case study, I searched for already available openly licensed content. I was fortunate enough to find a wonderful lesson on public health approaches to infectious diseases, which is the topic I wanted to develop. I took the sections that were relevant to my lesson and used it as is.

I designed the learning objectives and authored the case study on the 1916 New York polio epidemic. The case study was then incorporated into the already existing lesson. Using Soft Chalk, I divided the content into pages and added short answer questions throughout to keep the students engaged and to encourage reflection and critical thinking. This will also allow me to use the lesson as a graded assignment in my course.

In addition to the case study, I wrote a course description to use in my syllabus to let students know that I will be using open pedagogy approaches in the course. Contribution to the development of the case study and critical analysis of case studies from our book have been incorporated to the course as part of the grading criteria.

The student feedback was immensely helpful. I was worried about using Soft Chalk as a platform, but students really liked it and found it easy to use, even though they were using it for the first time. The students thought the case study was relevant and a great way to present the information. They did comment on some sections that may be too long and suggested the assignment/lesson reads more like a textbook. They recommended I incorporate more pictures and/or videos. One student reviewer suggested to have the lesson/case study narrated, so that it is accessible to students with a visual impairment. That was a great suggestion!

The students also mentioned that it would be great to have more information on the polio epidemic and more prompts for discussion. There are two areas where I plan to ask the students to contribute. They can do a bit more research on the New York polio epidemic and fill in the holes. They can also contribute with a bank of reflection/discussion questions, which was the original intent.

This experience has been fantastic for me. I have learned a lot, but I am also grateful for having gained a community of scholars that are passionate about education and who will become collaborators. I hope we can keep this going!

The Open Pedagogy Fellowship gave me the opportunity to make my courses more interactive, enjoyable, and, I hope, able to offer a richer learning experience for my students. It allowed me to explore contemporary pedagogical theory and practice in a convivial community of fellow instructors, and to learn so much from some very talented colleagues. It even provided us with a group of student readers who supplied useful feedback on our ideas in the summer before courses began.

As a result of the fellowship, my ARTS 2233 course, currently delivered online but returning to ‘in-person’ in Spring 2022, now adopts several new methods and materials intended to prioritize student learning rather than reward students for simply carrying out tasks. For example, I have all but abandoned deadlines and the traditional concept of ‘participation’ when they seem unnecessary, and many of the assignments are now ‘ungraded.’

The point of ‘ungrading’ is to allow students to focus on developing their skills rather than simply ‘doing the right thing’ to get a grade. All their weekly discussion posts are ungraded, but students receive feedback from me and from each other which helps them prepare and practice for two major assignments which are graded.

New course material now allows students to continue learning at their own pace outside the classroom, and without spending money on books. This includes films of live lectures I have made teaching in galleries, museums, and churches throughout Italy. Greater use of Canvas, Kaltura, and Zoom also helps to create a more flexible environment that promotes access, inclusion, and sustainability.

The biggest change I made was the incorporation of some hands-on activities that I hope will help students develop specific skills rather than simply acquire knowledge. First, they each choose and research an Italian painting in the Yale University Art Gallery in order to create an online in-depth guide to Renaissance art in New Haven.

Second, students co-create an online virtual collection of ‘tableau vivant,’ their own photographic recreations of Renaissance art. These lasting, publicly-accessible ‘open resources’ will also be useful to future students, a factor that I hope will stimulate my students and encourage them to take great personal interest and pride in their work.

I am sometimes very apprehensive about the new approaches I’m trying to adopt as a result of the fellowship, but, so far, students have reacted positively to the changes, and they tell me they benefit from the variety of resources, from the higher level of feedback they now receive, and from the ‘ungrading’ of the discussion posts.

Many students have also suggested ways to improve the course, and even this engagement in the pedagogy must be seen as another positive outcome. It won’t all be plain sailing, but I hope that by the end of the course I will learn much more from them about their experience with these new methods, and I am sure that their feedback will help me to keep improving.

This summer I had the opportunity to start my journey with Open Pedagogy. The amount of information and content was overwhelming at first, however with the help of colleagues, I learned how to sift through the information and started to create a “Communication Toolkit” website. This site will house resources (curated and developed by students) of different mediums/content that would help students with their communication skills.

As part of the process, I had student reviewers provide feedback on the website and assignments to coincide with the course expectations. Throughout this process I learned many things.

First and foremost, I learned that developing a plan helps to guide my process. At the beginning of the summer, we created a content map to help initiate the planning process. I created a content map that outlined the areas that I wanted my website to cover. I based it initially on my course modules, but as I built the site, I modified it to include the areas that I felt would be most beneficial for my students and their communication skills.

In addition to creating a content map, deadlines were developed that helped to ensure we stayed on track for creating our resources. My content map became fluid while I stayed on task with my due dates/deadlines.

I also learned that I often have grandiose ideas that need to be broken down into parts. Manageable chunks of content helped me to make progress instead of getting stuck on having “so much to do.” I learned how to make sure I stayed on track and chose manageable tasks that built upon one another. At times, I would get “stuck” on an idea and not know how to begin. This is when I would focus on my goal and backward chain the steps that are needed to get to the end goal.

One of the most beneficial lessons I learned is the value of student feedback. One thing we often take for granted is that we know our scope and have the background knowledge to be able to complete or understand something effectively.

Our students, however, don’t have this knowledge. I had seven student reviewers provide me very valuable feedback, and I didn’t realize how much I left ambiguous within my site description and assignments. For example, I used the term “external resources,” but never provided examples or a description of what I meant. I assumed that they would understand that I was looking for additional articles, videos, and other references to support a topic.

The student reviewers provided significant insight into my project and assignments that I would not have thought of on my own. I appreciate all of their feedback, from the site lacking excitement to concerns about ownership of blog posts. Their involvement is crucial to the success of this process within the classroom and I couldn’t be more grateful.

Overall, this process has been exciting and opened my eyes to the possibilities we have with Open Pedagogy! One thing that I feel that we could improve upon is helping to have student feedback at the beginning “idea/planning” stage and then further involvement once projects are created. Involving the students at the beginning of our process and throughout is key to a collaborative environment that will further increase their success.

This summer’s workshop on Open Pedagogy pushed me to develop an approach to teaching introductory history courses that escape the pattern I had settled in for a number of years: lecturing in each class period while students complete readings in two textbooks – a narrative chronological history and a book of primary sources – and then write a brief paper at the end of the semester.

This involved a complete rethinking about my aims for the introductory Core Curriculum Tier 1 history courses I teach. The experience I had teaching last year in the hybrid format (half of the teaching in the classroom and half taking place virtually) showed me that students definitely could write and share ideas with each other if given a conducive environment.

The smaller Open Pedagogy group meetings over the course of June and July helped give me the confidence that in class meetings this semester I could do things other than lecture. I developed an approach for my Open Pedagogy classes (I have two this fall, both HIST 1101 Being Human in Antiquity – formerly titled Foundations of the Western World) that focus on students in class accessing primary and secondary sources available online, learning how to select and read them, and then write about these sources.

In the last month of the semester, students will use what they had written earlier in the semester as springboards for a final course essay that will be posted on the course website, which I also developed this summer.

The student feedback on the writing assignments I developed was encouraging and gave me the confidence that my thinking on the assignment prompts (and the writing and rewriting of them!) was paying off and that students would easily understand and manage my assignments. The student feedback was especially helpful in enabling me to see where I needed to provide more structure in having students report to me what they were writing on.

My work this summer on these two sections in which I am using Open Pedagogy was also strongly influenced by my decision to apply a practice of “ungrading” – student work in these two sections will not be graded. I have pledged to students to provide timely feedback on their written work, and I will require that assignments be submitted on time. While students will determine their own grades at the end of the semester, they know I will reserve the right override their suggestion, though only if they cannot come close to justifying the grade they assign themselves.

As a result of this work with the Open Pedagogy Fellowship I am trying many new things this semester in these two courses. I hope that we, as Open Pedagogy faculty, can continue to meet, to share ideas, and to strategize in making our teaching effective in new ways.

I found the Open Pedagogy Fellowship and the incorporation of student reviewers into the creation of classroom materials invigorating. Over the last two years, I have asked students in my HIST 1000 classes to write articles on a public website with the intent that the site would then be used and expanded by future students. So, I was familiar with the idea of asking students to produce learning material, but I was not aware that this practice was just a small slice of a much larger pedagogical space called Open Pedagogy. The realization that there was a robust literature, spaces to share ideas, and whole communities of faculty willing to experiment and collaborate was both validating and taught me how much I still have to learn. The discovery of this wider pedagogical movement has definitely led me to be more ambitious with my own thinking.

For my summer project, I wanted to develop two sets of assignment prompts, one that would lead students to develop a personal statement about why the study of history matters to them, and a second set that would guide students to create videos that would teach future students a range of skills, from evaluating the quality of a website to essential techniques for analyzing primary sources. The hope is that future students could watch these videos produced by their peers and learn from them (and perhaps then create even better videos!). Eventually, I would like both the personal statements and the videos to live on this site.

I got some very valuable feedback from the students. Some of it showed me how hard it is to describe an assignment out of context! Typically, an assignment is given to students who have met you, been a part of your class, and have learned some important skills as well as your expectations. When writing an assignment, it is very difficult not to assume that your reader is in the same place as that hypothetical student.

Some of the student feedback revealed anxiety that I expected, such as with expectations for group work and how to be sure that each member is contributing equally, and whether new technologies would be taught in sufficient depth. Clearly, some student have had experiences where instructors have assumed knowledge of technology that students did not possess.

Some other pieces of feedback were less expected. Several student reviewers mentioned how much they liked knowing the explicit purpose and goal of the assignment up front, with no surprises. While the assignments I developed over the summer do not contain surprises, some of the game-based lessons that I sometimes use absolutely do. I may need to think more about how to communicate the learning purpose of a game while still preserving the necessary secrecy to make the game really work.

Another comment I need to think more about is the option to remain anonymous when writing for a public audience. Both of my new assignments ask students to put material onto a website, and some student reviewers said they would be more comfortable if they could post their material without their name attached. Students in my previous classes had not requested this, but perhaps they privately would have liked that option. On the other hand, I think it is motivating for a student to produce their best work when they know it will be out there for others to see.

Writing for a large audience is more authentic than just writing for me as the instructor. Is that still true if the author remains anonymous? It might, but it is clearly an issue I need to think and read more about. These comments about anonymity, however highlighted for me the value of the student review process this summer. Students who were already in my class (and thus perhaps already anxious about their future grade) may have been reluctant to share that kind of feedback.

I hope that student review of faculty materials can become a more regular feature of teaching at the University of New Haven.

This summer, I had the opportunity to participate in the Open Pedagogy Fellowship program to develop a module on Economic Analysis for Renewable Energy Generation in engineering courses.

The idea of developing this module started with a talk with a student, who was wondering if renewable energy generation can sustain without government subsidies. This question inspired me to introduce economic analysis in traditional engineering courses.

Besides knowledge delivered in the STEM classes, students are eager to get a full picture of the application and feasibility of the knowledge in practical applications through economic and marketing analysis. Especially in recent times, the need to develop low-emission and alternative energy resources drives wind and solar-generation construction all over the country. Large penetration of the new generation forms is changing the power industry’s landscaping.

In this Open Pedagogy program, I integrated a new module called “Economic Analysis of Renewable Energy Generation” in a senior course on Electrical Power Systems. In the module, I introduced: (a) the shrinking revenue that utilities are facing because the renewable generation reduces their electricity sales; (b) the business innovations that are emerging to take advantage of the new generation forms; and (c) how to do a cost-benefit analysis of investing in a renewable generation station.

I developed six submodules in this module:

Submodules 1-4 are mainly about the structure, content, and assessment of the module. Submodules 5-6 provide sample deliveries and a suggested timeline. The module is wrapped up as a course on Canvas and open to the public.

The Open Pedagogy program opens a door for me to access lots of free and interactive educational resources, such as how to get open textbooks and how to search open resources on Commons. On the other hand, developing OER also plays an important role in understanding the open resources, from license identification and platform selection, to content arrangement and presentation.

The last stage of student feedback is valuable. The student reviewers engaged in the module and provided comments from their perspectives. These comments help me polish the module from aspects of the content arrangement, language usage, assignments, and evaluation. I wish I had involved them from the beginning of the summer.

Overall, the Open Pedagogy program helps me learn what OER resources are and how to develop them. I will regularly check OER to find practices and resources for curriculum development. In addition, I would welcome regular meetings and opportunities to share with my Open Pedagogy Fellows even after the conclusion of our fellowships.

The Charger Blog

Beatrice Glaviano ’26 reflects on EMT life, learning assistant work, and what she hopes to carry into her final semester.

The Charger Blog

Katelyn Beach ’25, ’26 MBA reflects on her hands-in collaboration with the program’s founder and how Uccountability’s goal-setting and peer-based model can shape student growth, leadership development, and community at the University of New Haven.

University News

New University-wide council will advance strategic partnerships, immersive student opportunities, and innovative research, supporting the University’s strategic plan the development of its pioneering Center for Innovation and Applied Technology.